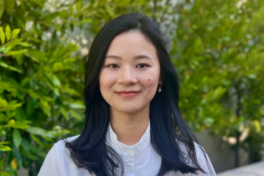

Qin Li is a political communication researcher and computational social scientist.

As a PhD candidate in the School of Communication, Li studies how society is vulnerable to incorrect political information via social media and in people’s offline environments.

“In my most recent work, I am looking at how people can get misinformed both through social media, but also beyond social media,” said Li.

Her primary research focuses on the impact of the information and social environment on factual beliefs, attitudes and behavior. She looks at how offline political and social contexts can explain why people get misinformed.

Li has work published in the Journal of Communication, Human Communication Research, PLOS One and Harvard Kennedy School (HKS) Misinformation Review. She was also selected to present at the National Communication Association Convention in November 2023.

Li’s research focuses on individuals’ belief sensitivity, or their ability to discriminate between true and false factual political statements. Her recent research published in the Journal of Communication shows that belief sensitivity varies based on whether a person lives in a battleground state and the state-level of partisan segregation.

Her research found that the difference between liberals’ and conservatives’ belief sensitivity is larger among people in battleground states than those in Democratic-leaning states during the 2020 U.S. presidential election, and that living in a less politically segregated state resulted in higher belief sensitivity during the election.

According to Qin, one of the most interesting insights is that people's ability to distinguish between true and false claim "varies by the offline political and informational context in a state, which has not been looked at in prior work.”

She concluded that the media environment, the campaign environment and the social environment people live in has an impact on their beliefs. In regard to the circulating misinformation in today’s news environment, Li said that traditional political communication channels, such as political campaigns and citizens’ everyday communication, are often overlooked in how they contribute to what people believe to be true or false in politics. Li said that these things are important when dissecting people's political behavior, including voting and collective action, as she observed in the last U.S. presidential election.

Although Li graduated from Fudan University in Shanghai, China, with a Bachelor of Arts in journalism, she ultimately strayed from the field due to the limited media freedoms in China and the inability to write an in-depth story under tight deadlines.

After traveling to Taiwan for a semester during her third year of undergraduate studies, Li developed an interest for the events and requirements that precede story-writing and her passion for conducting political communication research was born.

“With journalism, you spend little time on a topic, then move on, but with research, you spend more time on it,” Li said. “Having experienced the different political and media systems and how those impact people's political attitudes and behavior differently, I become interested in why people hold certain political beliefs and attitudes, and what role the information environment plays in shaping their attitudes.”

Li came to the United States with the intention to become a social scientist. She earned her Master of Arts in communication at Washington State University before starting her PhD at Ohio State. She said the graduate program at Ohio State won her over because of the abundance of resources and opportunities, the connections, the prestige and the academic environment.

Analyzing data and getting the results of a project is the most exciting part for Li, and it’s something that was missing when she studied journalism. However, the switch from journalism to research came with its share of obstacles.

Li said that being an international student has made the last four years of study particularly difficult, due to the pandemic and the political climate both in the US and China. She has not been able to travel back to China to visit her family since the start of her PhD program, even when her grandparents passed away. Additionally, Li said that the hostile relationship between the U.S. and China, the recent resurgence of anti-Chinese sentiment and the political repression in China, have all made it very difficult to be a Chinese PhD student studying political communication overseas.

“The most challenging part is the mental aspect of it all,” said Li. “In graduate schools, we tend to prioritize research and work but not attend to our personal needs. However, my co-advisors have always reminded me of the importance of taking care of myself, taking time to decompress, connect with my family, grieve, among others.”

Li said that she often spends time with her peers, whether that be listening to each other's concerns, providing and gaining advice, soliciting feedback from each other on their work, or doing fun activities together, such as playing board games, watching movies at Gateway, going to coffee shops or celebrating holidays together (including Chinese ones such as Lunar New Year and mid-autumn festival).

Post-graduation, Li hopes to land a faculty position at a research university to focus on research while also teaching undergraduate and graduate students. She has a desire to provide service and mentorship to students in addition to continuing her research.

Article by student Jadyn McRitchie